Bilingualism and Biliteracy

Aleko’s Adventures in Wonderland

On a Sunday afternoon, Aleko walked to the bookshelf in the living room and pulled a large leather-bound book. He skipped over to the couch and poked his father in the ribs to wake him up from his nap. His father blinked vigorously in an attempt to hide the evidence of his sleep. Aleko plopped himself next to him and put the book on his lap. His father rubbed his eyes one last time, placed his reading glasses on his nose, and began to read:

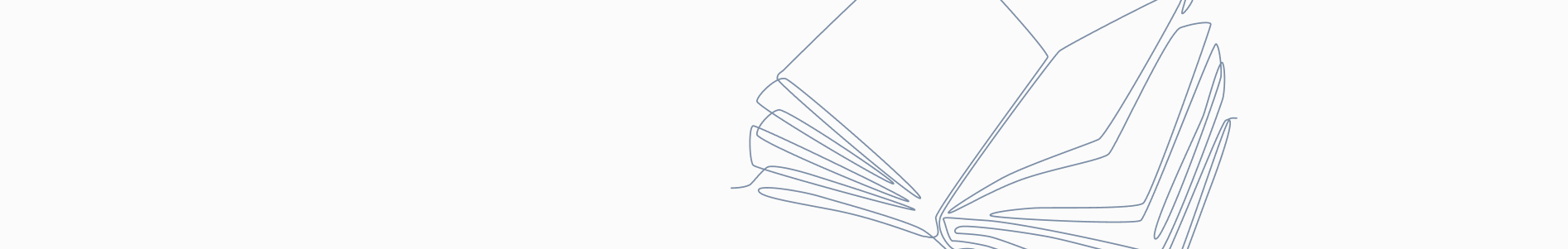

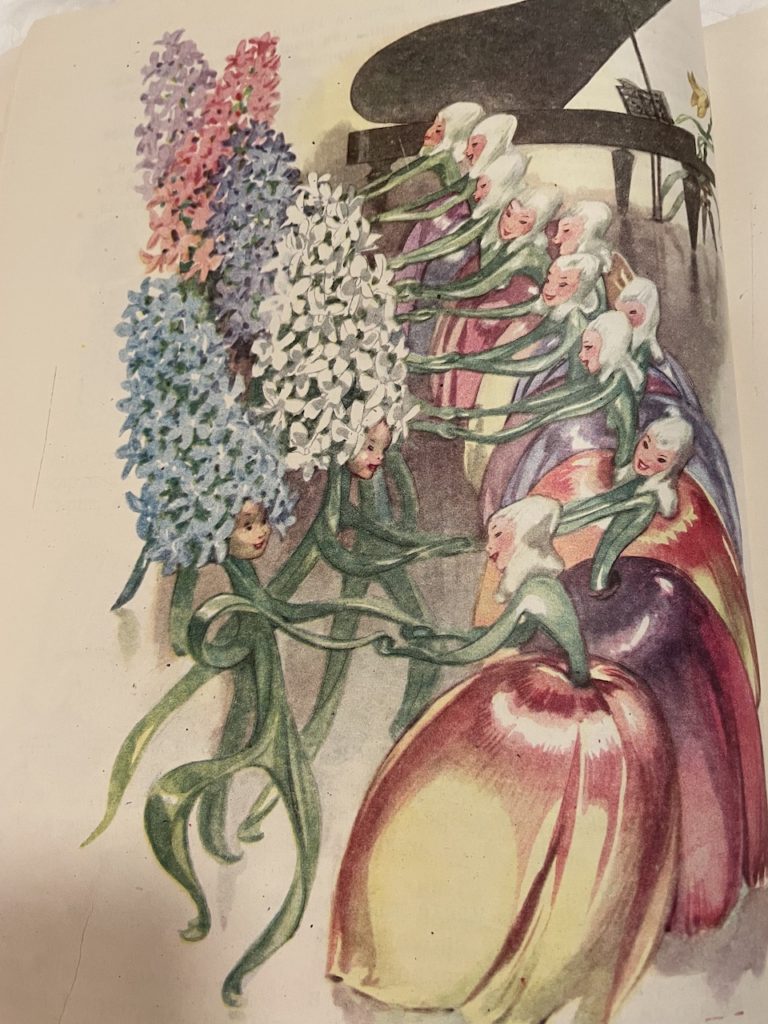

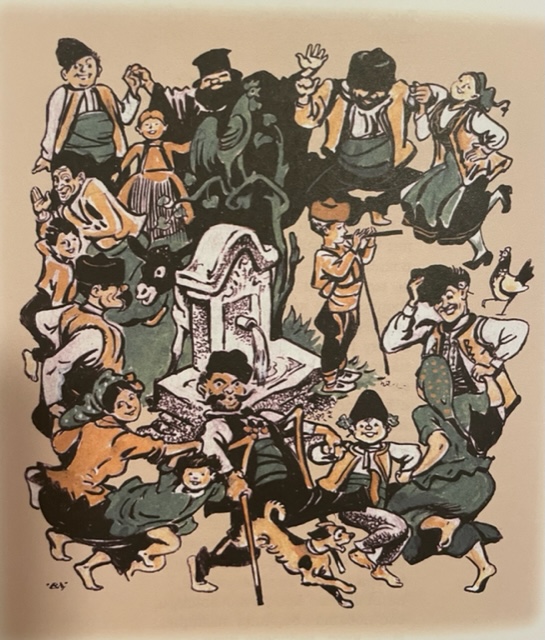

“Once upon a time . . .” At these words Aleko snuggled closer to his father and became transfixed by the beautiful illustrations on the pages of the book. As the story went on, the images began to move and Aleko followed them along their treacherous, arduous, or perplexing path. He was relieved and excited when they eventually got to the happy end.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Brothers Grimm

Puss in Boots

Charles Perrault

“Read more!” Aleko said as soon as his father finished the first fairy tale. And his father usually obliged him. Only later did Aleko realize that his father loved the stories just as much as he did. Aleko had learned which ones were his favourite. He knew that his father would be much more easily persuaded to read them. They were The Thousand and One Nights and the stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann (his most well-known story is “The Nutcracker” on which the eponymous ballets is loosely based).

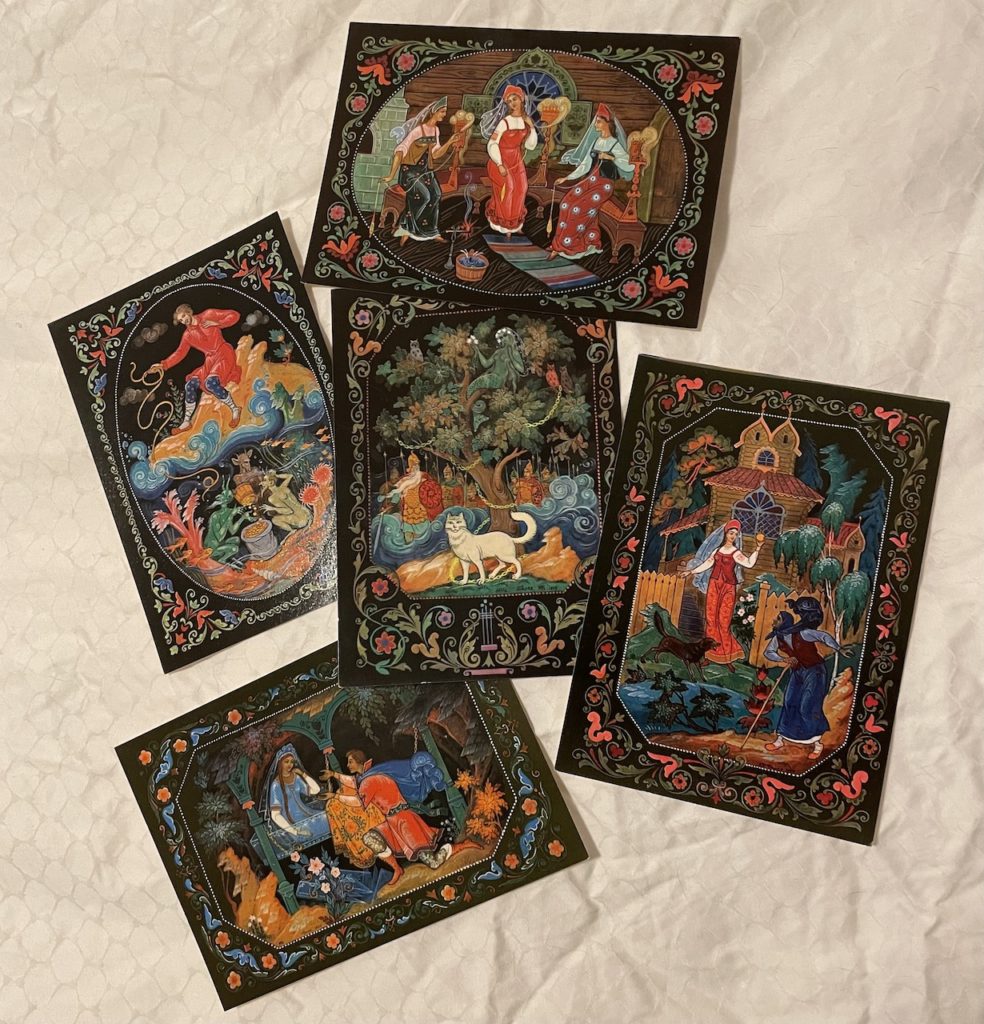

Aleko subjected his mother to the same harsh treatment too. But her favourite stories were somewhat different. They included Russian folk tales, such as the ones about Baba Yaga, and the fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen. As for Aleko, he didn’t care much for them because they usually made him cry. But he would still listen to them as often as his mother was willing to read them. When Aleko was five, all he wanted to know was what would happen next.

Little Ida’s Flowers

Hans Christian Andersen

French fairy tales

One day after his father had read for a while, and Aleko kept whining that he wanted more, his father said, “Why don’t you learn to read, and you can read them to yourself as often as you like?” Aleko was not nearly as excited about the idea as his father seemed to be.

For one, he had no desire to learn to read. Because while he was reading he would not be able to look at the pictures. And he loved the pictures, both on the pages and in his head. And second, most of the books in their home were written in Russian, and some in Italian and French. Aleko did not even speak the languages, let alone know how to read in them. His parents often simultaneously translated the books as they read them to him. He did not mind the sometimes-stumbling reading. Only later did he realize how good they were at this challenging mental task.

Little Aleko had learned, among other things, that some books were written in languages that he didn’t speak. And if he wanted to read them, he had to learn the languages first. And once he does, he would not only become bilingual, but biliterate, and even biscriptal.

The link between language knowledge and reading

Learning to speak a language in childhood tends to happen naturally, without the need of explicit instruction by a teacher. On the other hand, most children do not learn to read in the same carefree way. Instead, developing reading and writing skills takes a concerted effort and focused instruction over a few months, and in some cases even years. Children need to practice and dedicate time to reading at the expense of playing. As a result, reading has to quickly become a source of enjoyment and satisfaction in order for the child to remain motivated to keep reading. But sometimes the process of learning to read could be quite challenging. Children could become discouraged and lose confidence in their abilities, even without the presence of any language or reading delays.

The ability to read is strongly related to the children’s language abilities, because written language is a graphic representation of spoken language. In other words, children who have strong language skills are able to learn to read quicker and more effortlessly. We develop these language skills as a result of book reading or being read to.

Reading books increases the number of words children know, improves their ability to understand and produce longer and more complex sentences, and leads to greater familiarity with how stories are structured and what qualities make them more engaging. Therefore, children who are exposed to books early tend to be at an advantage when it comes to learning to read themselves. This is good news, because parents and caregivers could do a lot to prepare their children for the arduous task of learning to read and the rewarding task of enjoying reading.

Bilingual language proficiency and reading

Bilingual children often do not have equivalent abilities in both languages. They tend to be stronger in one language and weaker in the other. As a result, they would be at a possible disadvantage when learning to read in the weaker language. Their vocabulary sizes tend to be smaller, their grammar knowledge is less developed, and they often do not have sufficient experience with books and story-telling practices. Therefore, it is important for parents, as well as teachers, to be aware of this issue. They could provide the extra supports that bilingual children need to learn to read in their weaker language.

Reading is more than knowing the letters of the alphabet

The ability to read is a complex and multifaceted process. It requires a combination of mental skills. Therefore, simply learning the code, or the alphabet in the case of alphabetic languages, is not sufficient to be able to read well. Most broadly, reading comprises of two main skills:

- Decoding is the ability to recognize letters and their patterns, match them to their corresponding sounds, and ultimately sounding out the words that they make. It is the mechanics of reading, simply the ability to process print. Ultimately, good decoders could read out text quickly, fluently and effortlessly regardless of whether they understood its meaning or not.

- Comprehension is the ability to understand the meaning of the text. It is the more challenging aspect of reading, but it is ultimately what reading is all about.

These two main abilities are tightly connected and a good reader has to be strong in both. She needs to be able to decipher the code quickly and efficiently in order to then grasp the meaning. But children can have difficulties with either process, and in some cases with both. Bilingual children often have advantages in areas that ultimately help with decoding. But they tend to experience more challenges in the area of comprehension, which also happens to be the harder one to improve.

(with the ubiquitous water fountain that poured honey and butter, and the boy-shepherd)

Bilingual decoding

As discussed in my previous post on bilingual advantages, bilingual children develop better awareness of sounds. They gain earlier understanding that print is related to meaning. As a result, they are able to manipulate the sounds of language more easily. This skill, called phonological awareness, ultimately helps children learn how to read, especially in alphabetic languages. Once children realize that their spoken language is comprised of separate sounds, they are able to map those sounds onto the letters. They are able to decode text.

In the process of learning to read in different languages, bilingual children often tackle different orthographies and/or writing systems. In terms of orthography, languages fall into two main types:

(1) Shallow orthographies, where the correspondence between the sounds and letters is consistent and predictable (e.g., Italian, Spanish, Russian).

(2) Deep orthographies, where the correspondence between the sounds and letters is inconsistent and variable (most notorious example of this is English). Learning to read and write in a deep orthography tends to be more difficult than in a shallow orthography.

The two prevalent writing systems are alphabetic (the case of Latin and Cyrillic among others) and logographic (Chinese). They are based on different set of symbolic relations, and subsequently requires different cognitive skills. For example, mapping sounds onto letters tends to be a fundamental skill in learning to read in an alphabetic writing system. But it is not nearly as essential in a logographic writing system, which tends to rely more heavily on a more holistic and visual representation of meaning. Therefore, bilingual children would need to learn different skills and apply different cognitive processes when reading in each language.

Bilingual children develop pre-reading and reading skills differently than monolinguals. This fact presents them with additional challenges not usually encountered by monolingual children. However, bilinguals also benefit from their experience with two languages. Knowledge gained in one language could be transferred and applied to the other language. For example, if a child has developed phonological awareness in one alphabetic language (e.g., German), he could easily transfer that same awareness to the reading task in another alphabetic language (e.g., Russian). He needs to learn the skills in one language and only memorize the new code in the other.

Bilingual comprehension

Bilinguals do not have significant challenges with decoding, and in some cases, they could actually benefit from being bilingual. But they tend to experience more difficulties with reading comprehension. When bilinguals experience issues with the mechanics of reading, they tend to be malleable and short-lived. Their difficulties with reading comprehension, however, could be harder to detect, and could last for a long time, well into adolescence and even adulthood.

Reading comprehension is heavily depended on listening comprehension. Therefore, experience with spoken language is an important prerequisite to developing reading comprehension. In addition, our ability to understand text relies heavily on the number of words we know, among many other factors. But learning new words is not a quick and easy task. And more importantly, we tend to learn most words, especially rarer words, through reading.

Bilingual children often become fluent readers of a language. But due to weaker language proficiency, they tend to struggle with reading comprehension. Fortunately, by improving their language skills, and especially helping them enrich their vocabulary knowledge, we could do a lot to prevent them from falling behind their monolingual peers. Parents and teachers simply need to be aware of this challenge. They could also better prepare to help bilingual children develop the skills necessary to reach ultimate success in reading. And what is that?

Here’s my version of the “happily ever after”. To read a book while swinging in a hammock under the palm trees. Once you turn the last page, to smile at the satisfying end of the story or at the recognition of the new knowledge gained. And then, to tell you friends!